'Entrepreneurial': Natured or Nurtured?

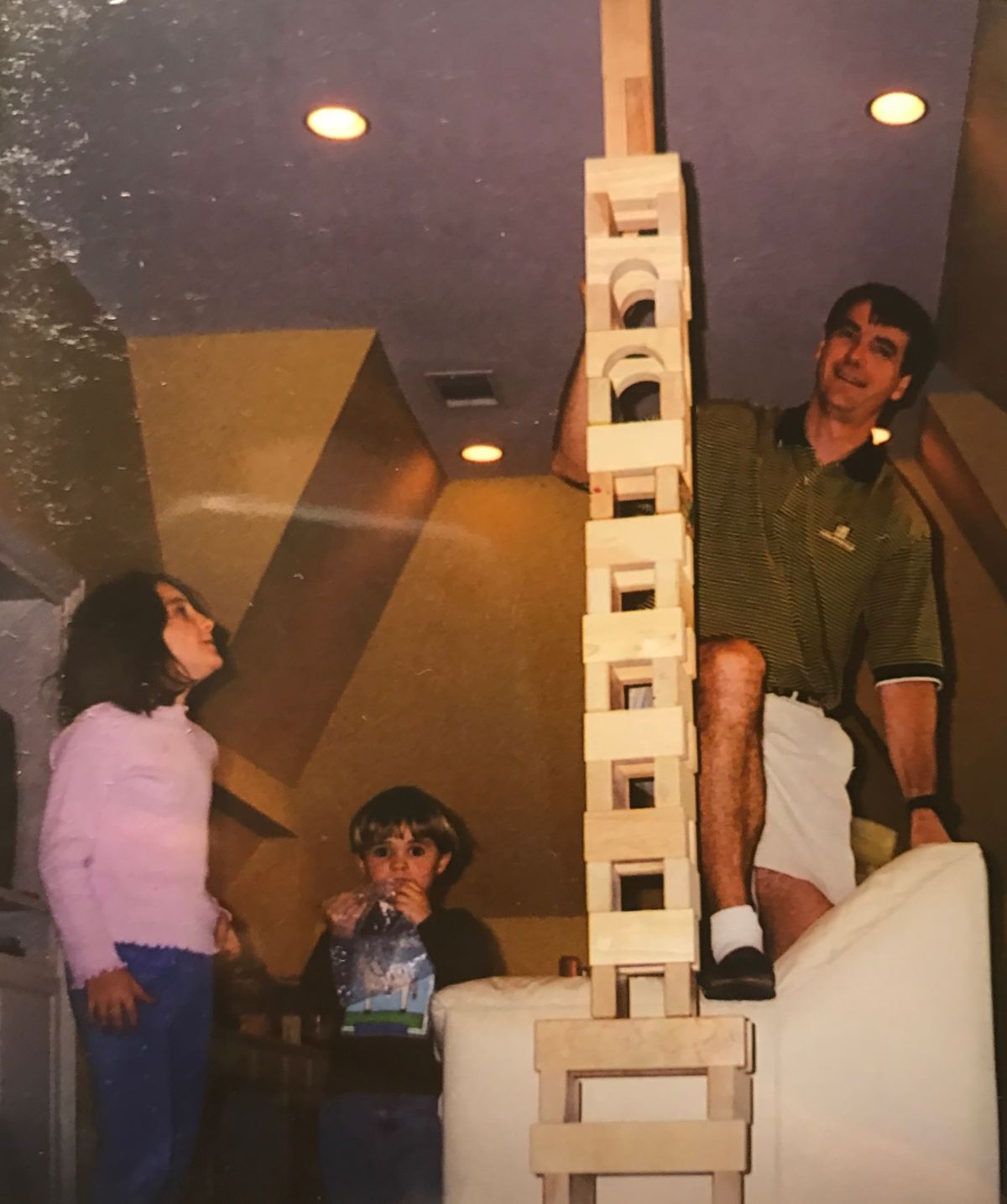

My dad was born an entrepreneur. When he was 7, he sold lemons and avocados from the tree in the backyard on the side of the street. When he was 11, he got a job as a paperboy that required him to wake up at 4am before middle school. In high school, he and his brother moved junk in the family truck, and during college he made money playing for two local bands. After business school, he turned down an offer from a sexy consulting firm to go work for his father-in-law at a coin-operated laundromat company in Texas. A decade later, my dad sold the company at the peak of the laundromats boom and opened a small real estate shop that he still runs today. In his 30-year career since Qwikwash (yes, he omitted letters before it was cool), he's led four companies; three have exited successfully. He loves strategy, “boring” industries and the art of investment. Like most kids feel about their dads, I have always thought he’s the smartest businessman I know. (Meanwhile, he ran more than 20 marathons, visited every US state, and, with my mom, raised four kids).

Are entrepreneurs born or are they made? Is there a certain level of conviction, predisposition to risk, or desire to be the boss that you just have or you don’t?

Contrast my dad’s career to my own: besides babysitting and a brief stint as a camp counselor (which I would have done for free), I didn’t have a job until after I graduated from high school, interned at some big tech companies, and went to Google as an APM. I achieved, and I did a lot of things I’m proud of, but in some ways I’ve accomplished less than my dad had before he was 10. Unless you count some small student clubs, I only have experience working my way up within organizations and have never started my own. Is it possible that I just don’t have “it” in me? It’s my dream to grow my own company, to lead product direction, but it’s much easier to race down a path someone else lays in front of you than to lay your own.

When I read stories about founders and technologists, they often talk about a childhood full of scrappy craft and entrepreneurship. Michael Dell was tinkering with computers in his first college semester and dropped out. Henrique Dubugras founded his first company when he was 16. Blake Mycoskie had three failed ventures under his belt when he founded TOMs. My adolescence, alternatively, was full of mostly normal prep-school scenarios: volunteer work, academic competitions, summer camp, a regular college degree, late nights studying for exams.

Of course, the only way to find out if I have the secret sauce is to try, and imposter syndrome doesn’t do any good for anyone. Last September, I started working on a video editing website called Kapwing with another X-Googler. Figuring out how to advance a startup is very different than figuring out how to get an acceptance letter or a competitive internship, but there is some similarity: how do you stand out authentically? How do you prove that you can add value in a unique and memorable way?

Every person is in some ways ordinary and in some ways extraordinary. If Kapwing makes it big, I’m sure I’ll look back and talk about overcoming early struggles, because those are the stories people like to hear. I’ll talk about the anxiety of forgoing a salary and bootstrapping an Internet company, of coding a platform from scratch, of dealing with sexist users, investors, and peers along the way. And if Kapwing doesn’t make it, no one will care about my stories, and I’ll resist the temptation of thinking I don’t have it in me to be as Great as my dreams are. In that way, I guess that entrepreneurship is a game of chicken with your own confidence and conviction, and nature vs nurture depends on how you tell the story.

The conclusion of this post is that you don’t need to be an immigrant, an early internet adopter, or a paper delivery boy to become an entrepreneur. How I Built This and the like might highlight the struggle and disadvantages of the people you admire, but they all had forces propelling them forward too, unfair advantages boosting them up behind the scenes. No one is destined to fall in line unless they choose to follow along.